Introduction

Modern parenting now comes with an unavoidable, glowing companion: the screen. Whether it is a smartphone soothing a fussy toddler in traffic or an educational video filling the gap between meetings, digital devices have woven themselves into the daily fabric of family life. Yet the very convenience that makes screens irresistible also raises urgent questions: How much is too much? What does constant digital stimulation do to a developing brain and body? This article unpacks the most significant negative effects of screen time for children and—equally important—offers practical ways parents can respond before technology’s benefits are overshadowed by its costs.

Understanding Screen Time in a Child’s Daily Life

Screen time includes every moment a child’s eyes and attention are captured by an electronic display: televisions, tablets, smartphones, computers, handheld gaming devices, and full‑size consoles. According to large‑scale pediatrics surveys, preschoolers today average roughly three hours of combined screen use per day, while teenagers can approach seven or more—often double what pediatric associations recommend.

Not all digital content is created equal. An interactive phonics game, used in moderation, stimulates problem‑solving and language centers; a looping reel of mindless videos does not. Educators therefore distinguish educational screen time—structured, age‑appropriate content designed to teach—from entertainment screen time, which prioritizes amusement and instant gratification. Both have their place, but parents need to track total exposure, context, and quality to maintain a healthy balance.

Developmental Impacts on Brain and Behavior

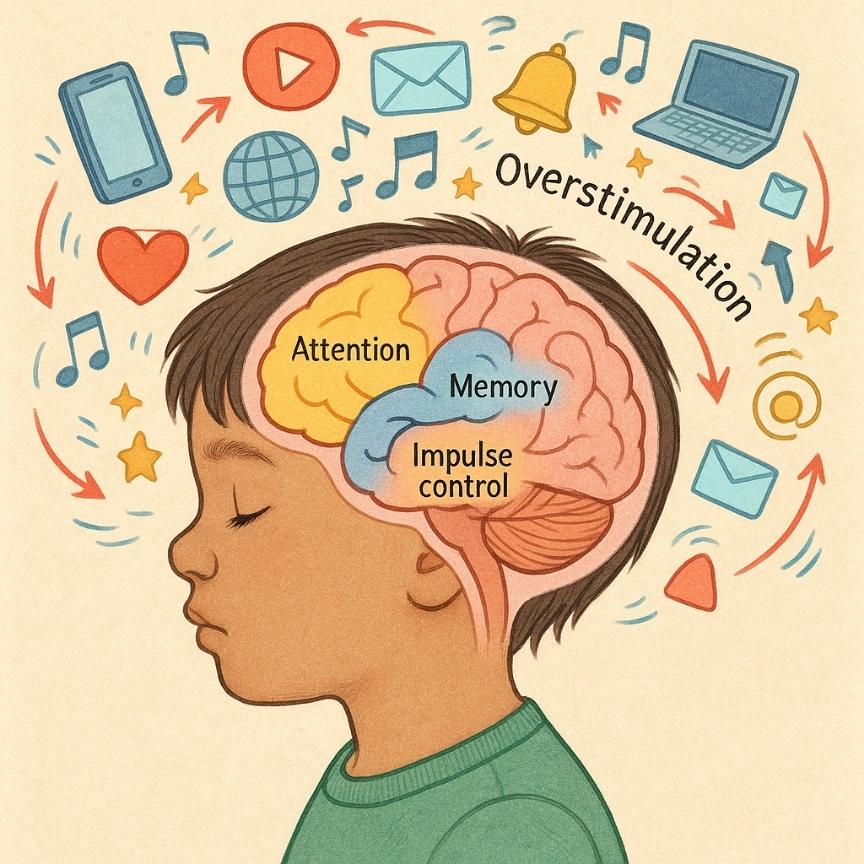

Brain development in early childhood is rapid, sculpted by every sight, sound, and social cue. Excessive screen time can hijack this process in three key ways:

- Attention span. Fast‑paced visual effects and unpredictable rewards—common in many apps and shows—train young brains to crave constant novelty. Over‑exposure has been linked to shorter sustained attention in both classroom and play settings.

- Learning and memory. When a child passively consumes content, fewer neural networks dedicated to deep processing are engaged. Research cited by the American Academy of Pediatrics shows that children exposed to heavy background TV score lower on language acquisition tests, suggesting that screen chatter can crowd out meaningful conversation and memory consolidation.

- Behavioral regulation. Studies have connected prolonged daily screen use with higher rates of irritability, impulsiveness, and hyperactivity. The World Health Organization notes that immediate dopamine hits from gaming or auto‑playing videos can make offline tasks—homework, chores, interpersonal dialogue—feel unrewarding by comparison.

Together, these factors may set a developmental trajectory that makes learning in a traditional environment harder and managing emotions more challenging.

Physical Health Concerns

Too much screen time is seldom sedentary alone—it is compounded by poor ergonomics and artificial light.

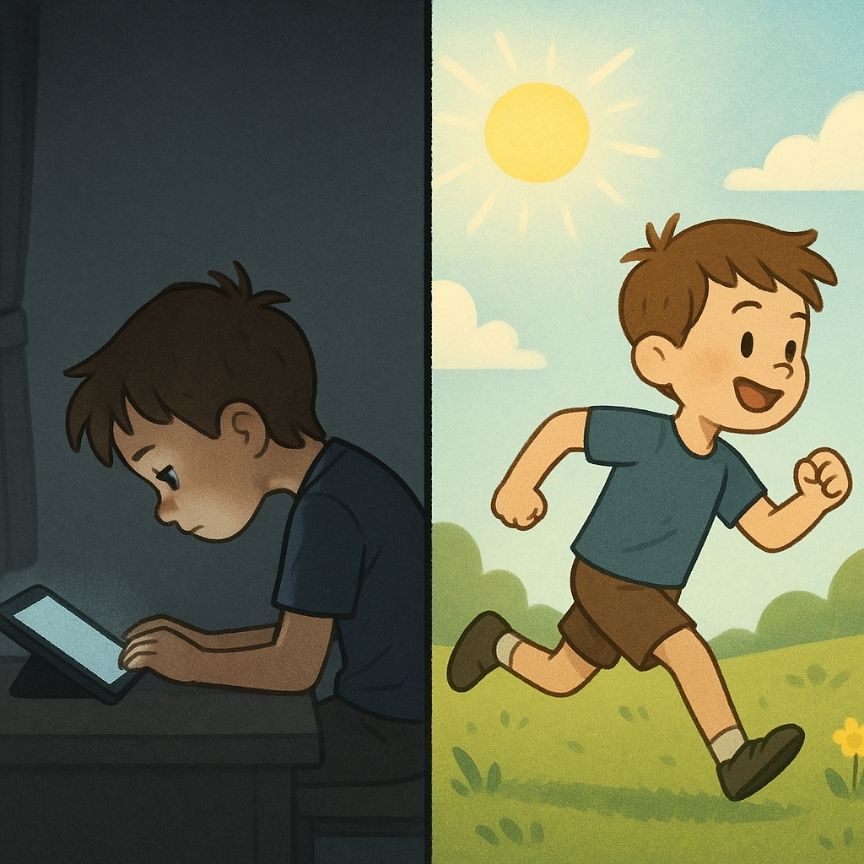

- Obesity risk. Extended sitting reduces caloric burn and often accompanies mindless snacking. Meta‑analyses tracking thousands of children demonstrate a clear association between hours spent in front of screens and higher body‑mass index percentiles.

- Eye strain. Staring at a bright display reduces blink rate, leading to dry eyes, headaches, and in some cases temporary blurred vision. Blue light emitted by LEDs has also been shown to disrupt circadian rhythms.

- Posture and musculoskeletal issues. Hunched shoulders, bent necks, and unsupported wrists place continuous stress on growing spines. Over years, this can manifest as chronic neck and back discomfort.

- Sleep disruption. Even brief evening exposure delays melatonin release; children persuaded to surrender a device just before bedtime often take longer to fall asleep and experience reduced restorative deep‑sleep cycles.

Counteracting these risks requires a two‑part formula: limiting cumulative screen hours and embedding daily movement—outdoor play, sports, or simple backyard games—into the family routine.

Social and Emotional Effects

Screens streamline entertainment but compress opportunities for face‑to‑face growth in empathy, negotiation, and nuanced communication.

Reduced interpersonal interaction. Time spent texting or gaming cannot simultaneously be spent reading facial cues, resolving real‑world conflicts, or building conversational patience. Over years, this deficit can manifest as awkwardness in group settings and discomfort during unstructured play.

Emotional regulation challenges. When a tablet or TV show is the default pacifier, children miss chances to practice self‑soothing skills—deep breathing, imaginative play, or seeking comfort from a caregiver. Consequently, frustration thresholds lower, and emotional outbursts may increase.

Content concerns. Even “kid‑friendly” platforms can expose children to hyper‑stimulating visuals, aggressive advertising, or themes beyond their developmental readiness. Overstimulation, in turn, may contribute to anxiety or desensitization to violent imagery.

Building emotional resilience requires pulling attention back to tangible experiences: board games that teach turn‑taking, shared chores that foster cooperation, and downtime for boredom—because boredom sparks creativity.

Parental Challenges and Practical Solutions

Balancing work demands, household tasks, and children’s cravings for digital entertainment can feel like negotiating with a tiny tech startup CEO. These strategies help restore control without outright bans that often backfire:

- Define tech‑free zones and times. For example, no devices at the dining table or during the final hour before bedtime. Physical cues—charging stations outside bedrooms—set clear boundaries.

- Create a daily media plan. The American Academy of Pediatrics offers templates; parents can customize by age, ensuring essential needs—sleep, homework, chores—are scheduled before screen allotments.

- Use co‑viewing and co‑playing. Watching a science documentary together allows parents to pause and discuss, turning passive watching into interactive learning. Likewise, multiplayer games can become cooperative problem‑solving sessions if adults participate.

- Leverage built‑in tools. Most devices now feature screen‑time dashboards, automatic shut‑offs, and content filters. Adjust these settings to reinforce agreed limits, reducing the need for constant policing.

- Offer compelling offline alternatives. Stock art supplies, build a home reading nook, rotate toys, or set up mini adventures—like a backyard scavenger hunt—that outshine the allure of a glowing rectangle.

- Model healthy habits. Children mirror adult behavior. Parents who scroll absent‑mindedly during conversations inadvertently teach that screens outrank people.

Introducing these measures gradually—one habit at a time—prevents resistance and helps the whole family transition toward a more balanced media diet.

Conclusion

Screens will remain part of childhood: they educate, entertain, and connect. Yet when unmonitored or overused, they can shorten attention spans, encourage sedentary lifestyles, strain young eyes, and blur vital social cues. The good news is that technology’s downsides are not destiny. With conscious choices—steady limits, active supervision, and plenty of offline opportunities—parents can turn screen time from a stumbling block into a manageable tool. Small, consistent adjustments today lay the groundwork for healthier bodies, sharper minds, and stronger family bonds tomorrow.