Introduction

Responsibility is one of the quiet superpowers of early childhood. Long before children can spell the word, they discover that actions have consequences and that tasks need finishing—even when a grown-up isn’t watching. From putting blocks back on the shelf to feeding a classroom hamster, these small acts teach children that they are capable participants in their own lives. A well-nurtured sense of responsibility builds self-confidence, sharpens executive function, and prepares kids to work kindly with others. Just as important, it helps them understand that community runs on cooperation, not commands. This article unpacks what “responsibility” means for a child, why it matters for intellectual and emotional growth, and how adults can encourage it without crushing curiosity or play.

Featured Image Prompt Words: Bright preschool classroom, diverse children taking turns watering plants, natural sunlight, candid photography, warm tones, high-resolution photo

1. Defining Responsibility in Early Childhood

In developmental terms, responsibility is the child’s emerging ability to recognize obligations and follow through. It blends three skills: awareness (“This needs doing”), initiative (“I’ll start”), and persistence (“I’ll finish”). A toddler begins by copying parents—placing a spoon in the sink or handing over a diaper. By age four, many children can anticipate routines such as packing their own backpack. What distinguishes true responsibility from simple obedience is internal motivation; the child acts because it feels right, not just to avoid reprimand. Early educators often use visual cues—picture charts, color-coded bins, daily rituals—to help kids link tasks with ownership. Over time, these cues become internal prompts, laying groundwork for self-regulation in homework, friendships, and eventually work life.

2. Why Responsibility Fuels Cognitive Growth

When a child decides to feed the family pet or finish a puzzle before playtime ends, the brain lights up in regions tied to planning, sequencing, and working memory. Neuroscientists have shown that purposeful tasks strengthen the prefrontal cortex—the “air-traffic control” center that coordinates thought and action. Repetition cements neural pathways, turning once-effortful chores into efficient habits. Meanwhile, accomplishing a task sparks dopamine release, the brain’s natural reward signal; children feel proud, which reinforces the behavior. Responsibility also integrates left- and right-brain functions: logic to remember steps, creativity to solve hiccups (e.g., when the puzzle piece seems missing). Over months and years, this mental workout translates to better problem-solving, longer attention spans, and smoother transitions between activities—skills every teacher celebrates.

3. Emotional Intelligence and Accountability

Responsibility is inseparable from emotion. Handing in a worksheet on time can spark pride; forgetting it can trigger guilt. Learning to ride these feelings builds emotional intelligence. When adults respond with empathy—“It’s frustrating when we forget, but let’s think of a reminder system”—children practice naming emotions and taking corrective action. They learn that mistakes are information, not identity. This outlook fosters resilience: children who clean spilled juice without melting down are more likely to tackle bigger challenges later. Importantly, a responsible child doesn’t suppress feelings; they recognize, regulate, and redirect them toward solutions. Parents can model this by apologizing when late or explaining how they plan to fix an oversight. Seeing grown-ups own errors normalizes accountability and demystifies the repair process.

4. Social Responsibility: Cooperation and Community

Beyond personal tasks, children must grasp their role in a group. Cooperative responsibilities—passing scissors, waiting for a turn on the slide, or voting on the next storybook—teach democratic living. Research shows that classrooms where chores are shared boast fewer behavioral issues and higher peer approval ratings. Collective tasks also combat “spotlight syndrome,” the belief that one’s own needs outrank others’. When a five-year-old helps set the snack table, they witness how effort benefits peers, not just self. Community projects, such as planting a garden or staging a charity bake sale, magnify this lesson; children see tangible outcomes that ripple outward. Over time, social responsibility nurtures empathy, bridges cultural differences, and empowers kids to envision themselves as change agents in wider society.

5. Stages of Responsibility: Age-by-Age Milestones

Responsibilities should expand with competence, not merely chronology. Ages 2–3: simple one-step tasks—putting toys in a bin, carrying socks to the hamper. Ages 4–5: two-step sequences—clearing dishes then wiping the table, feeding a pet then recording it on a chart. Ages 6–7: personal hygiene and time management—laying out clothes, brushing teeth without prompts, starting homework. Ages 8–9: community contributions—taking out recycling, helping cook simple meals, tracking reading logs. By age 10+, children can manage allowance budgets, plan parts of a family outing, or mentor younger siblings. Matching task to ability keeps challenges in the “stretch zone,” where effort breeds mastery without overwhelming. Celebrating progress—stickers, high-fives, genuine words of appreciation—cements the link between responsibility and positive self-image.

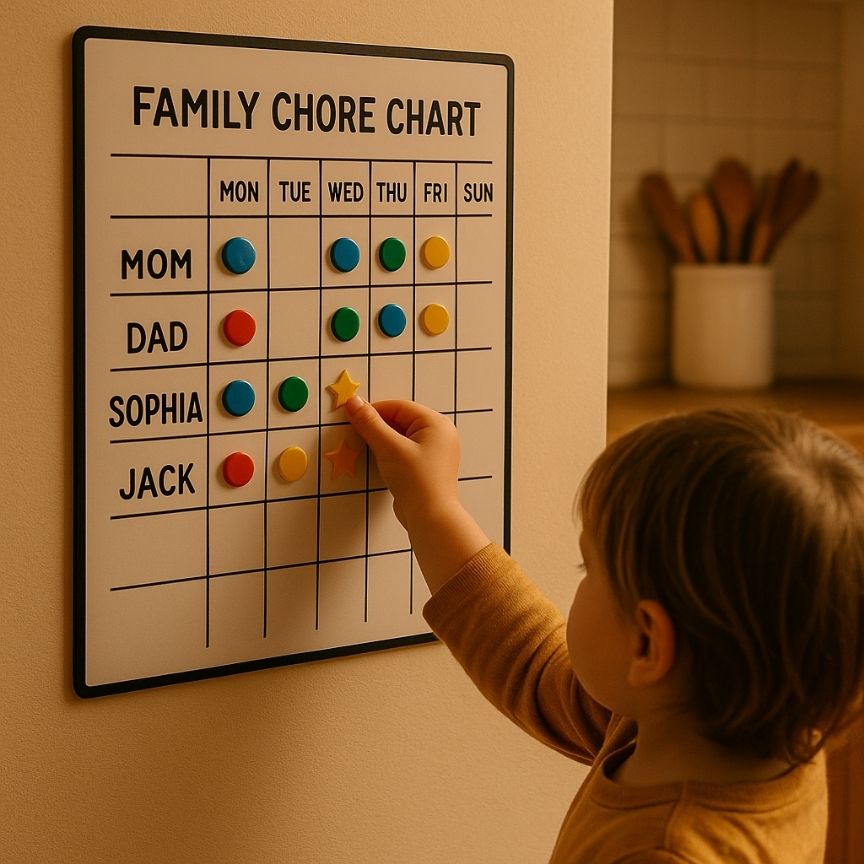

6. Cultivating Responsibility at Home

Home is a child’s first micro-society. Parents can foster ownership by creating predictable routines, labeling storage, and offering limited choices (“Would you like to water the fern or fold towels?”). Consistency is key: tasks must recur to become habits. Equally important is granting meaningful autonomy—resist re-folding slightly crooked towels; perfectionism crushes initiative. Family meetings where children help set weekend chore lists teach negotiation and follow-through. Technology can help: smartwatch timers remind children to practice instruments; chore apps provide gamified rewards. However, intrinsic motivation grows when tasks tie into family values: “We recycle because we care about Earth,” not merely “because Mom said so.” Finally, empathy-rich feedback—praising effort, identifying roadblocks—guides children to refine strategies and rebound from lapses.

7. Responsibility in the Classroom

Teachers translate domestic lessons into academic and social arenas. Job boards rotate roles—line leader, tech helper, attendance monitor—so every child experiences both leadership and service. Project-based learning pushes students to divide tasks, set deadlines, and peer-review work; here, responsibility intersects with collaboration and critical thinking. Mistakes become teaching moments: a forgotten supply list prompts discussion on contingency planning. Educators also embed responsibility in digital citizenship—citing sources, respecting online privacy, curating credible information. Schools that integrate service-learning (e.g., neighborhood clean-ups) report higher civic engagement years later. Importantly, assessments should credit both product and process, valuing steady effort over last-minute heroics. Through these structures, the classroom becomes a laboratory where children experiment with responsibility and witness its academic dividends.

Conclusion

A child’s sense of responsibility is not a single trait but a living skill set that grows through practice, feedback, and meaningful purpose. Nurtured wisely, it strengthens cognition, shapes emotional resilience, and weaves children into the social fabric with confidence and care. By matching tasks to ability, modeling accountability, and celebrating effort, parents and educators hand children the tools to navigate a complex world—a world that urgently needs citizens who see what must be done and step forward to do it.