Introduction

Responsibility is the quiet engine that powers trust, productivity, and personal growth. From remembering homework in grade school to honoring deadlines at work, the ability to take ownership of tasks and their consequences shapes how we are perceived and how we perceive ourselves. Yet responsibility is not a single switch flipped at adulthood; it develops in layers, guided by brain maturation, social expectations, and deliberate practice. Understanding that progression helps parents, educators, managers, and individuals nurture it more effectively. This article unpacks what “developing responsibility” really means, why it matters, and how you can cultivate it—whether you are mentoring a five-year-old or leveling up your own professional game.

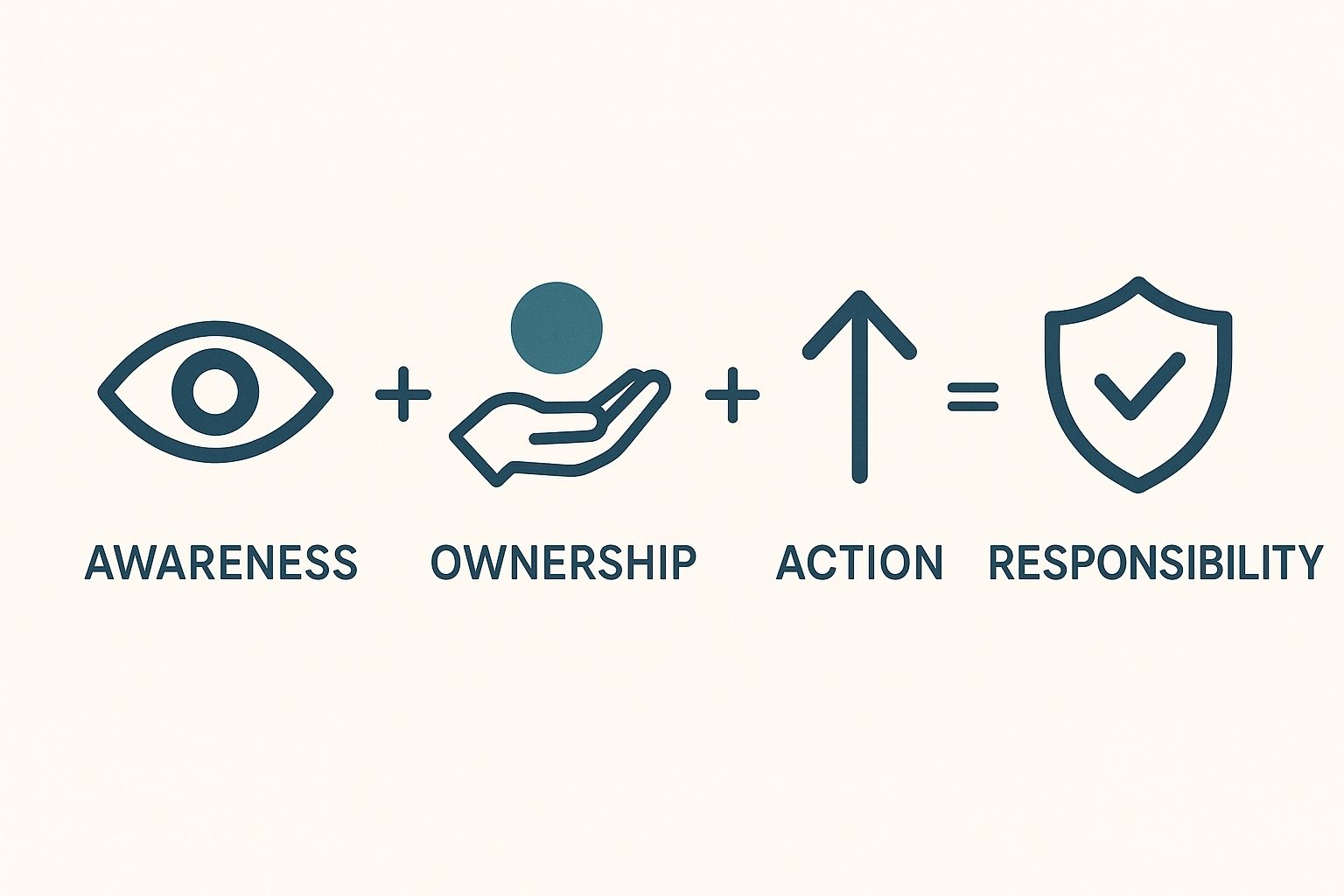

1. Responsibility, Defined and Deconstructed

Responsibility combines three interlocking abilities: awareness of what needs doing, ownership of the outcome, and action to see it through. Awareness without action is just observation; action without ownership breeds blame-shifting; ownership without awareness invites overwhelm. When all three align, you get accountable behavior—admitting mistakes, solving problems, and following through even when no one is watching. Psychologists sometimes call this blend “internal locus of control” because the individual believes their efforts actually influence results. A person with an external locus may shrug off chores, thinking “it won’t matter” or “someone else will fix it.” Cultivating an internal locus early on lays the groundwork for consistent, self-directed responsibility across life stages.

2. The Developmental Stages of Responsibility

Early Childhood (Ages 3–7)

Young children start by mimicking adult routines—putting toys in bins, feeding pets under supervision. At this age, responsibility is choreographed: an adult breaks tasks into micro-steps and offers visible praise for each success. The goal is to link effort with positive impact (“When I water the plant, it stays alive”).

Middle Childhood to Pre-Teens (Ages 8–12)

Cognitive leaps in planning and memory let kids manage multi-step projects: assembling tomorrow’s school bag, finishing group assignments, or budgeting weekly allowance. Natural consequences (forgetting a lunchbox means a rumbling stomach) teach better than lectures. Encouraging reflection—“What went well, what will you change?”—turns mistakes into learning moments.

Adolescence (Ages 13–18)

Identity exploration collides with peer pressure, so responsibility must connect to personal goals: balancing a part-time job with grades because it funds a desired gadget or college dream. Here, logical reasoning allows teens to foresee long-term repercussions, yet the emotional brain still seeks novelty. Mentors should set guardrails but allow calculated risks.

Emerging Adulthood (18+)

University, vocational training, or first careers mark the shift from supervised to self-managed accountability. Success hinges on habits built earlier—time management, financial literacy, ethical decision-making. At this stage, accepting feedback and practicing self-regulation cement responsibility as a lifelong trait.

3. Internal Drivers: Values, Motivation, and Mindset

Values act as a compass, steering choices when external supervision fades. For example, a student who values honesty will credit teammates in a group project even if shortcuts beckon. Motivation can be intrinsic (satisfaction, curiosity) or extrinsic (grades, salary). Research shows intrinsic motivation yields more durable responsibility because the reward is self-generating. Finally, mindset—whether you see abilities as fixed or expandable—shapes perseverance. A growth mindset interprets setbacks as cues to adjust strategy, not proof of incompetence. To strengthen these internal drivers:

- Clarify core values. Family discussions, journaling, or corporate workshops help articulate what matters.

- Set meaningful goals. Link tasks to personal ambitions to ignite self-propulsion.

- Celebrate effort as well as outcome. This emphasizes controllable actions, reinforcing ownership.

4. External Catalysts: Family, School, and Community

No one develops responsibility in a vacuum; environments either reinforce or erode it. Families that delegate age-appropriate chores send the message “you are capable and trusted.” Schools that pair freedom with accountable deadlines teach time management better than last-minute penalties alone. Coaches and club advisers who give teens real stakes—organizing a charity run, directing a play—provide safe arenas for trial and error. Communities, meanwhile, model collective responsibility through recycling drives, neighborhood watches, or disaster-response drills. The common thread is scaffolded autonomy: guideposts are visible, but individuals choose paths within them.

5. Building Responsible Habits: Practical Strategies

- Use visual organizers. Calendars, kanban boards, or mobile apps externalize commitments, reducing mental clutter.

- Break big tasks into checkpoints. Completing segments delivers mini-dopamine hits that sustain momentum.

- Implement the “two-minute rule.” If a task takes less than two minutes, do it immediately to prevent backlog.

- Practice reflective debriefs. After finishing a project, spend five minutes asking what worked, what didn’t, and one tweak for next time.

- Set up natural consequences. Rather than rescuing a child who forgets gym clothes, let them sit out the activity once; reality teaches faster than reminders.

- Model publicly. Leaders who admit mistakes (“I missed the client’s email—here’s how I’ll prevent that next time”) normalize accountability.

- Reward consistency, not heroics. A steady track record of on-time reports outweighs an occasional all-nighter miracle.

Implemented steadily, these tactics rewire routines so responsibility becomes reflexive rather than effortful.

6. Overcoming Barriers and Setbacks

Even committed individuals hit roadblocks: procrastination, perfectionism, burnout, or external crises. The key is distinguishing obstacles from excuses. Procrastination often masks fear of failure; tackling the hardest sub-task first (the “eat the frog” method) breaks paralysis. Perfectionism, ironically, can erode responsibility by delaying delivery; adopting “good-enough first, refine later” preserves momentum. Burnout signals systemic overload—redistribute duties, inject rest, and reassess priorities before engines stall. Finally, life upheavals (illness, layoffs) may temporarily lower capacity; transparent communication prevents misunderstandings and keeps trust intact. Resilience is thus the safety net under developing responsibility: when you fall, you rebound equipped with insights rather than shame.

Conclusion

Developing responsibility is less a destination than a perpetually evolving skill set. It starts with tiny acts—tying shoelaces, returning a borrowed book—and scales into leading projects, families, and communities. By aligning internal values with external scaffolding, practicing concrete habits, and rebounding from setbacks, anyone can expand their capacity to own outcomes and honor commitments. In a world where reliability is currency, nurturing responsibility—within ourselves and those we mentor—is both an ethical duty and a practical investment in future success.